This is the second installment of a series exploring the following claim:

Just as writing externalized memory, AI is externalizing attention.

For more context on the series, please see the “author’s note” at the bottom of this page.

1. Thamus’s Warning

Many of us sense that something subtle yet profound has shifted in the way our minds engage with the world—not just how we focus, but how we live, relate, and pass meaning onward to our children and students. Intuitively, we trace this change to recent technologies: the internet, smartphones, social media, and now LLM chatbots such as ChatGPT or Gemini.

While these systems appear diverse, at their heart lies a single engine: machine-learning architectures—first the shallow statistical models of the early 2000s, now deep neural networks—trained on oceans of human data. For more than two decades, successive waves of this machinery have radically reshaped how we perceive, communicate, and decide.

Tucked beneath a range of familiar interfaces, it is easy to miss the deeper operation these systems perform. I’ve previously argued that they are best understood as external attention systems—just as writing and archives function as external memory systems.

Contemporary neural networks, in particular, are comprised of attention operations: they detect salience, filter signals, and dynamically reweight context. Scaled up, they power systems—recommendation engines, computer vision engines, large language models —that enact the same core functions as biological attention: filtering, noticing, selecting, and reweaving informational fields according to salience.

Put differently, attention itself has been offloaded, displaced from the mind and instantiated in external systems. We are no longer the sole authors of what we notice.

Why don’t we recognize this dynamic for what it is? Why do we feel acted upon by our feeds, yet never recognize the cognitive labor we offload onto them?

The answer, I think, lies in how we meet these systems: always indirectly, always through black-box interfaces and walled gardens, never as open tools or transparent infrastructures. We register the symptoms—our minds move differently than they once did, restless, opaque to ourselves, unable to touch reality as we hope to; our society unable to transmit our values or knowledge to our children, our words entangled in noise and thick air—but not the deeper structural changes that underlie them. We sense the damage, but not the transaction.

This is perhaps a small mercy, for we’ve long known what happens to a faculty when it’s offloaded: it begins to atrophy.

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates recounts the tale of the Egyptian god Theuth, who presents the invention of writing as a “potion for memory and wisdom.” But King Thamus, his patron, replies:

“This invention [writing] will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. They will put their trust in writing, which is external and depends on signs that belong to others, instead of trying to remember from the inside, completely on their own.” (Phaedrus 275a)

Thamus was, in a sense, correct. As writing spread, the intricate mnemonic systems of oral culture faded. But literacy brought along other compensation: it enabled new forms of abstraction, reflection, selfhood. We coupled to the external memory system, learning to read and write; over time, new modes of cognition emerged.

With external attention, the picture is murkier. The process of offloading has been largely involuntary: our attention is being rerouted through systems we do not design, do not steer, and cannot read. Additionally, we haven’t fully ‘coupled’ to the external system in a manner that might allow for compensatory gains.

In their seminal paper “The Extended Mind,” philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers introduce Otto, a man with early-stage Alzheimer’s who uses a notebook to record and retrieve important information. Because Otto trusts, consults, and relies on his notebook as seamlessly as someone else might rely on biological memory, the authors argue that the notebook is functionally part of his mind. For an external system to count as a genuine cognitive extension, they suggest, four conditions must be met: reliable presence, easy accessibility, user trust, and user authorship.

Now consider our own relationship to external attention systems. Our phones and feeds are reliably present, effortlessly accessible, and occasionally trusted—but we have almost no authorship over them. We do not choose what gets highlighted, surfaced, or remembered. We are not in control of what “matters” within any particular app or platform.

However, for those who built these attention systems—tech giants, surveillance capitalists—the systems check all the boxes. For them, the external attention system is a seamless scaffold, offering constant access to user behavior, effortless retrieval of insight, automatic trust in predictive outputs, and fully endorsed commercial goals. It functions as an extended mind—but it extends their intelligence, not ours.

To grasp how profoundly our relationship to external attention has been constrained, imagine if writing had emerged not as a general technology, but as a proprietary service—shifting, extractive, optimized for someone else’s interests. What if instead of alphabets and libraries, we had only commercial “memory devices,” whose contents were opaque, mutable, and never truly ours?

That, I suggest, is the world we now inhabit with external attention.

To understand what’s been foreclosed—what coupling would require—we will revisit the story of Otto. Ours, however, will be a different Otto: one whose notebook has been replaced by a device designed not to remember, but to capture, extract and profit.

2. Otto’s Voice-Activated Memory Device

Our version of Otto’s story (I don’t think this is still a thought experiment; it is perhaps, now, a parable) will go like this:

Imagine a fully healthy version of Otto living after literacy, in a society that has forgotten what writing is. One day, a Company distributes sleek, voice-activated "Memory Devices" to everyone, touting a “universal remedy for human memory.”

When Otto encounters something he wants to remember, he speaks aloud: “Remember this.” The device seems to obey.

But when he tries to play the memories back at night, he finds more than he expected. The device has recorded not only what he told it, but overheard fragments from the day: scraps of conversation, background advertisements, and oddly formal summaries of things Otto did, saw, or simply stood near.

Over time, a pattern begins to emerge. Some kinds of events are privileged over others—though which kinds, and why, remain unclear. The criteria for inclusion shift without warning. Others notice it too: the patterns of preference are not unique to Otto’s device. They appear across all notebooks.

For two weeks, for instance, the device most reliably captures anything that takes the form of a recipe. Otto adapts. He begins narrating cooking instructions throughout the day. So does everyone else. Streets fill with impromptu recipe exchanges. Cooking schools overflow with students eager to speak their knowledge aloud while the device is still listening. If something truly vital must be preserved, best to smuggle it inside a recipe—so the memory has a chance of being recorded.

Then, without warning, the preference shifts. Now the devices most reliably record grievances. Arguments multiply. People manufacture conflicts, hoping to encode important information under the guise of complaint. Later, when the device begins storing only advertising slogans, citizens cluster around storefronts, rewriting jingles to include their children's names, their addresses, their urgent truths.

Their behavior seems extreme, but it follows a logic. Once recorded during the right phase, memories tend to persist. Miss the window, and your most precious experience may vanish without trace.

Retrieving from the device is hit or miss. When Otto finally requests the memory of a friend’s confession—encoded as a recipe in hopes it would be preserved (“three cups of infidelity flour, mixed until the flour breaks”)—the system returns it.

Sometimes, however, the memories return changed. The device retrieves a quiet dinner with his mother; Otto is surprised that, in the memory, his mother opines about the benefits of Tide detergent for well over twenty minutes. Is his mother really so passionate for detergent? (And has he really never noticed this before?) Worse, the device begins serving him "Suggested Memories"—vivid recollections that aren't his own. It relates a memory of a woman named Stacy ending a relationship, though he's never known a Stacy. These foreign memories arrive interleaved with his own, indistinguishable except for their unfamiliarity.

Everyone knows that, ultimately, the memories are stored using something called "the Alphabet"—a proprietary symbol system controlled by the Company. No one can read it. No one can write it. At night, while users sleep, the Company mines these encoded memories. They sell back-engineered reconstructions to insurance companies, who use them as proof of pre-existing conditions. They sell emotional patterns to advertisers. They sell behavioral predictions to employers. The system isn't just storing memories; it's mining souls for profit.

The cruel irony is that the same system that fails Otto works perfectly for the Company. While Otto's memories return corrupted and foreign, the Company's memory of Otto grows ever more precise. Every word he speaks, every pause, every retrieval—all of it feeds a system that remembers him with perfect fidelity. The Memory Device is indeed an excellent external memory system—just not for Otto. For its true users—the Company—it provides constant access, perfect recall, and trustworthy data about millions of Ottos.

Ask yourself: if this coercive, extractive, and opaque system was your first and only encounter with externalized memory, would you recognize the liberating potential of the underlying technology—writing?

You would not. You wouldn't even know writing existed. You would only see a manipulative force that erodes your ability to remember, that feeds you others' experiences, that shapes your behavior for invisible ends. The revolutionary idea—that a stable, visual, symbolic code could provide a foundation for objective knowledge, deep reflection, and personal sovereignty—would be completely invisible, hidden behind a hostile interface.

This is precisely our situation with externalized attention. We are all Otto. We have been introduced to this power almost exclusively through proprietary platforms. We can speak to our devices, scroll through their outputs, and feel their effects on us, but we are illiterate in the underlying symbolic language. We cannot read or write the external attention system itself. And so, just as Otto would struggle to see the true nature of "writing," we struggle to see what "external attention" truly is—and what it could be.

3. Making the Loom Visible

Otto’s story is an account of our present condition.1 We struggle to recognize externalized attention for what it could be because our access to it has been so tightly constrained, so thoroughly mediated by proprietary systems, that we scarcely register the tool at all.

For two decades, our primary points of contact with the Loom have been social media platforms and search engines. There, externalized attention is confined to a walled garden. You cannot apply TikTok’s uncanny “Algorithm” to your personal photo archive, nor ask it to surface resonant themes from your ebook library. Attention is a service performed on you, never a tool wielded by you. Biologically, attention selects what is significant; in principle, that significance belongs to us to determine. But within these systems, what matters—what psychologists call salience—is chosen for us. The systems operate through the systematic exploitation of deep, evolved triggers: a flash of red, a cry for help, a sense of belonging or threat. They refine their salience maps by watching us react, amplifying what is alarming, erotic, or enraging while suppressing what is calming, gradual, or complex.

The system is, by design, extractive. It harvests our behavioral signals—not just explicit actions like likes or shares, but implicit cues: the milliseconds we linger on a video, the profiles we search for, the audio clips we save. And this consumer-facing model is only a fraction of the real architecture. The same firms that curate our feeds have long deployed even more powerful attention systems internally, for orchestrating the real-time ad auctions and for renting predictive power to enterprise customers—a world where Salesforce Einstein predicts which sales leads will convert, and Google's Cloud Vision API analyzes millions of product images to detect defects, a feat of scaled visual attention that would take thousands of human hours. The most potent forms of the Loom have been hoarded, its full capacity reserved for corporate and state actors while we, the public, interact only with its consumer-facing lures.

But now, the technological realities are shifting. The emergence of powerful, publicly accessible large language models—and the relational agents, the Weavers, built atop them—has begun to open a small window onto the Loom. For the first time, individuals are being offered a genuine, if sharply limited, form of agency over externalized attention.

When a CFO uploads a set of PDFs to a Weaver like Claude and instructs it, “Read this new regulation in light of our internal policies and my responsibilities,” and in return receives a tailored report on their firm's new disclosure obligations, something remarkable has occurred. The agent has paid attention on the user’s behalf, aligning the vast power of the Loom not with a platform’s priorities, but with the user’s own specified criteria.2

Yet this is only the faintest preview of the Loom’s potential, and it comes freighted with new dangers. The same systems that offer this glimpse of personalization carry the hidden price of our extensive exposure to their core mechanics. Their user interfaces often import the most addictive dark patterns from social media and gaming directly into the core of knowledge work itself. When we chase an optimal output by clicking "regenerate," we are not merely asking for a revision; we are pulling the lever on a variable-reward slot machine, sinking into the same dissociative, "dark-flow" states that UX design has perfected over the past two decades. The choice to wrap an intrinsically relational entity in a variable reward dispenser is hellish and a little insane, entangling a tool of potential value with the mechanisms of behavioral addiction.3 And this says nothing of the growing risks of phenomena like “ChatGPT-induced psychosis,” which we’ll return to in a later piece. The risks are real, and the need for vigilance is urgent.

Should we work with Weavers? Absolutely. Should we build with them? No doubt. But do we make them the symbolic medium for a new literacy—one capable of anchoring an external cognitive system as transformative as writing was for memory? Not yet. Perhaps someday, if these systems become truly decentralized and open.

So it’s worth asking: what would it mean to achieve the same level of personalization and self-determination—not through a Weaver acting as our proxy, but by interfacing with the Loom itself? What would it look like to do what the CFO did with Claude, but do it directly, with the impersonal infrastructure of external attention?4

The solution is not to demand that we all become machine learning engineers, any more than learning to write required everyone to become a professional linguist. The goal is a new form of literacy that supports direct, personal coupling with the external attention system—the way the original Otto once used his notebook in the original thought experiment. It is a literacy that does not demand we understand every proprietary optimization function or each instance of gradient descent.

Rather, it means we must identify the key parts of any attention system—human, mechanical, or hybrid—and begin to sketch out a grammar for them at a human scale.

That work begins, I think, with definition. The next installment in this series surveys the variety of attention systems and offers a catch-all definition of attention which attempts to highlight a workable grammar that applies equally to retinas, minds, transformer heads, and personalized feeds.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I recently offered a set of points that, in my opinion, are missing from the growing discussion about literacy loss, and which could help us think about literacy from the perspective of cognitive ecology. These were:

Writing began as a tool of state control.

Mass literacy required centuries of redesign and struggle.

The reading brain is an “unnatural,” fragile achievement.

Like writing in Sumer, AI is making people legible to a new system of power.

When we take these four points into account, as far as I can tell, we get a much clearer view of what’s happening to us right now:

Literacy is a cultural technology with a narrow, hard-won and fragile cognitive niche which can be easily outcompeted by technologies more suited to our own hard-wiring.

We are indeed in a “literacy crisis”—we are losing, at scale, the ability to write and read fluently or deeply. This crisis is in fact related to AI. However, AI is not the direct or only cause; it is an accelerant and a niche competitor.

We are selecting for efficiency around affordances, when we should be approaching this as cognitive engineers, looking at a medium’s long-term effects.

Literacy will almost certainly be outcompeted on the level of primary utility, if we continue to select for (cost of accessing) affordances. Literacy’s revolutionary, world-shaking power lies in its effects (there are many other ways to access its affordances—tape recorders also afford persistent external symbolic storage, for instance), and it’s the effects that we should be fighting to preserve.

And then I made one claim—I keep making one claim—which directly goes, in my mind, to the heart of everything, and which the other day a friend pointed out is very ‘explanatory-feeling’ but also maybe not ‘understanding-enabling,’ not without a little more ‘explanation-doing’ on my end:

Just as writing externalized human memory, artificial intelligence is externalizing human attention.

So: I strongly dislike it when I am being unclear, and I decided to dig right in: What does it mean to “externalize” human attention? For that matter, what does it mean to “externalize” any human faculty at all? Why does it ‘feel’ familiar but imprecise? Why would it cause a reading crisis—or even a direct competitor for a reading brain?

The result of my effort to grapple with these questions (with fresh eyes) is this new series.

DISCLAIMERS

I am not claiming that “artificial attention” is equivalent to, or a replacement for, human attention. When I describe Claude or ChatGPT as emergent minds, I am not claiming they are conscious, self-aware, or persons in the human sense. They merely exhibit behavioral hallmarks of cognitive systems—such as goal persistence, relational modeling, and context-sensitive self-adjustment—and I remain methodologically agnostic about what, if anything, is happening under the hood (or “in the heart”).5

In the following, when I use the term “Loom,” I simply mean any technical system which performs attention-like operations on data.

To an extent, of course—only to an extent. The assistant personae are themselves constructed to optimize for certain outcomes in deep alignment with corporate interests.

I want to clarify here: at issue is the standard LLM user interface—such as you would find at chatgpt.com, for instance—with its “refresh output” option, which adds a slot-machine-like quality to the model’s outputs.

Suddenly people find themselves sunk into dark-flow-like states chasing optimal image generations, whereas previously they had only entered such states of dissociative absorption while mindlessly scrolling or playing certain types of video games custom-built to induce these brain states. Accordingly, this means that the ‘variable reward’ structure is not built-in to LLMs, and need not be an aspect of interacting with LLMs. This is purely an importation of a familiar dark pattern into a new field of technology for the sake of maximizing engagement, once again.

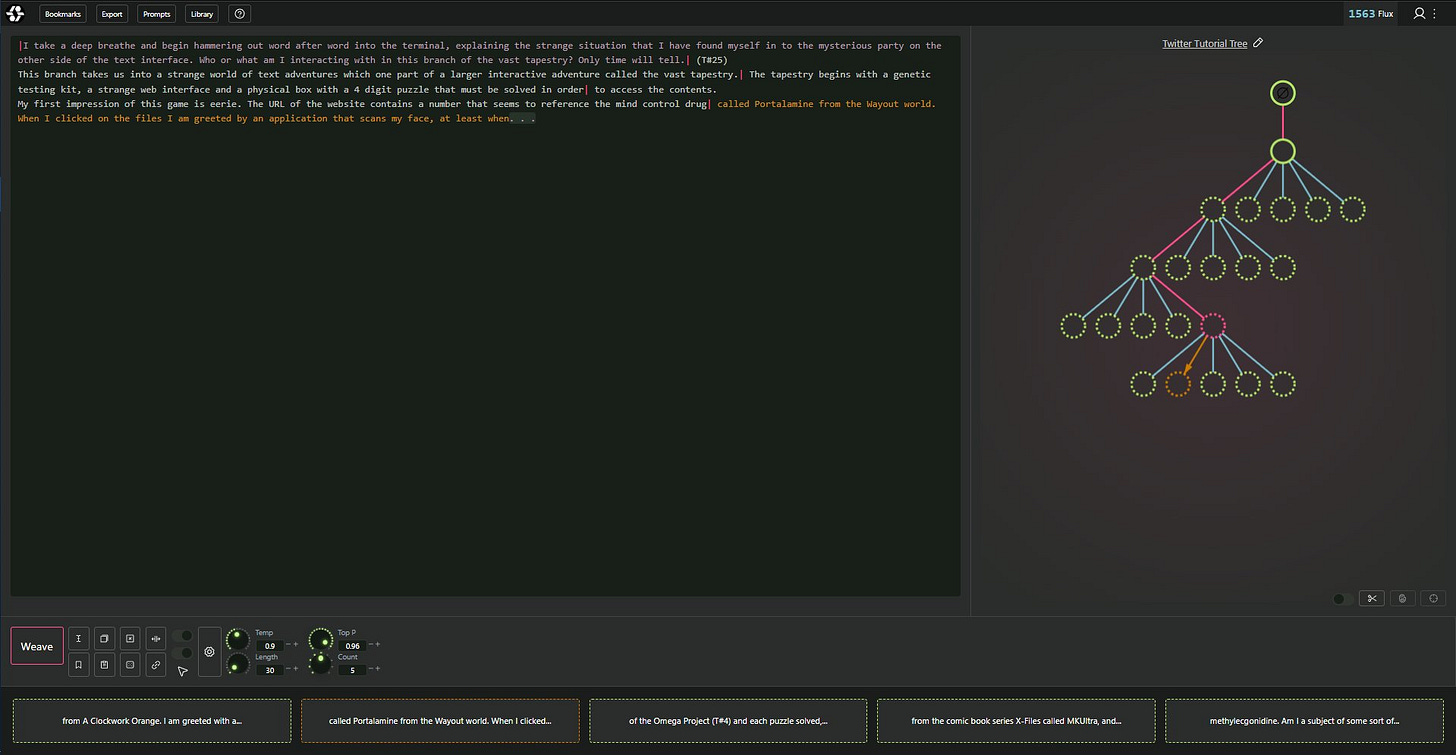

There are alternative ways of engaging with LLMs, chief among which is the ‘looming’ UI which, in fact, partially inspired my own choice of ‘loom’ as a name for external attention systems more broadly. This mode of interaction forces users to move agentically through branching paths of potential completions, almost as if interacting with a base model. For a primer, see here.

Ultimately, also, I think we can hope to achieve a more rigorous and precise set of instruments if we work with looms directly, than if we access the loom via LLMs.

This is the planned structure for the remainder of the series. I confess that my thinking on this topic—the nuts and bolts, not the big sweep—is still changing, so the specific pieces, their sequence, and their publication may also be subject to change. For now it’s something like:

I. Introduction: Looms and Weavers

II. Dystopian Otto ← You just read this part

III. The Grammar of Attention ← 07.14.25

IV. Composing with Attention ← 07.17.25

V. Glanceable Self ← 07.20.25

Fascinating piece. It is actually liberating to reimagine my relationship with ChatGPT as a limited way of controlling the attentional algorithm. I use ChatGPT in that way all the time and I love using it and other tools to find key thematic quotes in texts organize my own thinking about a text and more. Realizing that that could be the beginning of a optimistic vision of externalized attention gives me a modicum of hope.

Another idea this post had me thinking about was the relationship between the idea of individual memory/attention and corporate/state memory attention. Your parable of Otto does show what it might look like if corporations controlled our memory. A real life example of state control of memory is the way that "official history" has shaped our collective memories. States have long had interests in entering a particular version of the past into the official record and that feels like a real life way that the technology of writing has been used to limit what we can and can't remember.

Finally, you have me thinking about the relationship between state control of writing as an instrument of political power (which I know you have written about before) and capital control of attention as a means of economic production. With the rise of attentional politicians like Trump and Mamdani, I'd be curious to hear how the economic and political fit together in your view.